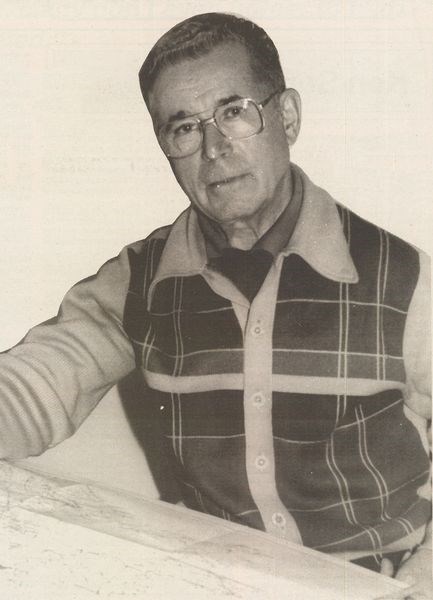

In November 1990, which was 25 years before he died in June 2015, Alex Drancejko of Kamsack spoke to the Times about his youth when he survived the “Harvest of Sorrow” in Ukraine, and then was pulled into the Second World War.

A quiet, slight and somewhat aloof man, Drancejko, when interviewed for the story, said that a day does not pass without his being reminded of his horrible youth.

As the community assembles to remember the sacrifices made by veterans of war, the experiences of Drancejko, a retired baker, deserves to be remembered.

Following are excerpts from the original story that was published in November 1990.

“For 48 years I had wanted to share this with someone, but I always though the time wasn’t right,” he said. “I feel relieved to have finally said this, but unless you were there, to see it, have it in your skin, you won’t know it.

“Having told this story, I bow my head, pray or hope that the many millions, not hundreds of thousands, but millions, between six and 10 million people perished; I hope, at least they will rest in peace.”

Drancejko said that it was his fate that as a seven-year-old he had lost his parents and a brother to starvation. He had not seen his two sisters since the day they were forced onto a train, heading east.

Drancejko was one of the few persons alive in 1990, maybe only 50 in Canada, he said, who had witnessed the forced famine of 1933 in Ukraine.

He survived when a quarter of the rural population of Ukraine, the men, women and children, estimates as high as 10 million “lay dead or dying, the rest in various stages of debilitation with no strength to bury their families or neighbours.

“Remembering, sometimes I feel like I’m being ripped open. I know what it means to be hungry. It is something you can’t know unless you’ve experienced it.

“I hope never again this will happen, not to seven-year-olds, not to anyone,” he had said during the interview in the kitchen of his Fifth Street home. “Nobody realizes how painful is dying from hunger. It is the worst death to experience.”

Until about the time of the interview in 1990, Drancejko had been silent. He said he had feared that if he had spoken out, retribution might have been taken out on those he left behind in Ukraine: his sisters, if they were alive or his many cousins, because added to the agony of his experience was having to live in a world in which the experience was being denied. The official Soviet government position on the incidents which took the lives of millions of Ukrainians was that it did not happen.

“I want to expose the famine,” he said. “I’ve wanted to for a long time.”

Drancejko came to Canada from England in 1952. After working in bakeries in Swan River and Lynn Lake, Man., he moved to Kamsack in 1961 when he purchased the former Woodwards’ Home Bakery, a business he owned and operated until poor health, the result, most probably from years of deprivation, forced him to sell in 1971. He got a job as a clerk in the Kamsack liquor store, retiring in 1986.

Of his earliest years, those before his seventh birthday in 1933, Drancejko remembers very little. He has little recollection of his parents. In fact, it was not until he was an older child that he learned that the person he had called his mother was his mother’s sister.

Born in Western Ukraine, about 500 kilometres southwest of Kiev in a small village near Kamianets’ Podil’s’kyi in 1926, he was one of four children of Helen and Alex Drancejko, who were farmers.

A new political era had begun. The Communist Revolution had successfully dispensed with the old guard and a new order was being attempted. Josef Stalin succeeded Vladimir Lenin in the Kremlin and Stalin and his associates attempted to crush two elements seen as irremediably hostile to the regime: the peasantry of the USSR as a whole, and the Ukrainian nation.

Drancejko, his two sisters and an older brother, were orphaned at the beginning of the famine. They were raised by his mother’s married sister Oxana and were treated as her own.

Of his mother, Drancejko had learned that she had died in 1932 in a jail on the island of Solovetskiye, just off the Baltic coast. Very few people ever returned from that island, he had learned. His mother had been banished after having been jailed many times, having been caught illegally crossing the border to and from Poland, risks that were taken in order to visit a sister.

“They would use any excuse to put us away,” he said, explaining that his maternal grandfather had divided his 10 hectares of land among his eight children. Although only small landowners, they were landowners nevertheless, therefore they had “a little more.” They were seen as being ‘above” others. They all could read and write.

As the economic squeeze got tighter, Drancejko’s father gave his piece of land to his wife’s youngest sister, who was married, but still with no children. In exchange, she had agreed to tend his four children while he went to find a job.

“I still don’t know the whole story,” he said. “My father was not strong. He was in poor health when the collectivization started. He returned home in the fall of 1932 and passed away before Christmas.”

The authorities had divided the four children. He remembers the day when he, his two sisters and brother, were taken to a train station.

“My older two sisters were accepted on the train, My brother and I were turned away. He went back home with me. He was the oldest; I, the youngest. He was supposed to keep an eye out for me and maybe he did that job too well.”

That was the last time he had seen his sisters. Later, after he had gone to school and learned to read, he received a letter from one of them saying that one sister was living in Kursk, the other in Orel, both in Russia.

“I don’t know if they’re alive. I don’t know what they did.

“I called her my mother,” he said of his Aunt Oxana, as he set the scene to tell of the famine in 1933.

“It was poverty all along. Nobody had enough to eat, ever.”

Drancejko is an avid reader who speaks Ukrainian, Russian, German, Polish and English, so he has been able to place his recollections into the correct political and historical context.

His first remembrances of oppression are of the Russians “or people trained in Russia; special people, who knew how to search, find, look” for the increasingly scarce, hidden food.

Forming the collective farms, Stalin had wanted to take the land away from the property holders, he said. “The cities had food, but they were guarded by the police to prevent the peasants from coming in. Stalin wanted to starve out the peasants.

“It wasn’t much, but our family had land.

“The taxes were made higher and higher. The farmers were told to give so much grain, then were told to deliver more, and more until there was no more.

“They were forced to hide the remaining food under floorboards, behind walls, in secret cubicles concealed between rooms, anywhere away from the officials.

“I remember a woman had bread baking in the oven, and they took it. They would come, from one village to the next. One man was armed. They searched for the food, and took it away.

“It was bad, but in 1933, that’s something else, something you don’t forget.

“In the spring there were hardly any gardens. The people had eaten everything during the winter so there was nothing left to plant. The first to die were the older people, and the children. When spring came, April and May, I remember watching the funerals. I was sitting outside watching the people go by. Our house was on one of the roads to the cemetery.

“First there were three, four or five funerals a day, then more and more. And our house was on only one of several streets going to the cemetery. Later on, there was no counting the funerals.

“At first the dead were buried in wooden coffins, a board from here and one from there; later, bodies had to be buried in sacks or whatever.

“You see, whoever had worthwhile boards, traded them for bread.”

He and the other neighbourhood children had survived by digging in the fields at the collective farm, finding shriveled potatoes rejected from last year’s harvest.

“We’d dry them in the sun,” he said, explaining that they would grind the dried potatoes, make the grinds into patties, cook and eat them.

“Upstairs in the barn there would be straw and buckwheat chaff that had been used for feeding the pigs. We mixed the chaff, particularly the buckwheat chaff with the potatoes to make a pancake. But soon, there were no potatoes left.

“People ate anything. Everyone had small mills in the house. They’d grind corn cobs in them to make a flour. Gardens were soon bare of weeds, those plants having been eaten. Wheat, still soft and milky, was ripped from the growing, green plants.

“As kids we would eat anything that was eatable. I’m not ashamed to tell what I did and what I ate.

“And we’d steal from the collective fields. Because of that we were still alive.”

He told of having “chicken’s blindness,” a condition resulting from when the body is deprived of food. The eyes lose their ability to see in the dark, he explained. “When the sun goes down, you’re blind.”

His brother died in May or June. Ten years older than Alex, he had been “maybe too careful, giving me more than he should have.”

He weakened and starved to death.

“When you die of starvation, you either swell or dry out. I was swelling from the beginning. He was skinny.”

One of his aunt’s children died about the same time as his brother.

“The village became like a cemetery: quiet. There were no dogs or cats left. If the people had been allowed to have guns, there’d have been no birds either, but firearms were forbidden.

“Bodies were left here and there. Someone died under a fence, that’s where he stayed.

“Later, towards summer, work parties were organized to pick up the corpses early in the mornings, before anyone could notice them.

“No strength was left to cry. We were so weak.”

Although the 1933 harvest had stopped the famine, things could still not be described as better.

“Sure, we had potatoes, black bread and soup; okay, but we had no meat, butter, cheese or milk. There was virtually none of that.”

Drancejko was one of about 10 children who had been admitted to the village’s orphanage and he went to school until June 22, 1941 when war against Germany began.

While at school, he had been working at the collective farm, helping the man in charge of the horses. The Russians had wanted to evacuate the horses from the collective farms so he and some of the other boys were given five or six horses and were told to take them to the next town, about 20 kilometres to the east. The fighting came while he was on that trip.

Because the Russians were retreating from the Nazis, the authorities had left, so there was no one to receive the horses.

“We left them in the pasture and decided to return home, but those horses got home before we did. They had been feeding along the road and we pretended to chase them. The Russians were retreating fast, trying to stop us from returning, but we kept going towards the Germans. We didn’t know anything. I was 15.”

He, his village and Ukraine were caught up in the shooting. Germans were firing on Russians, Russians were firing on the Germans.

Under sporadic fire, and eluding the armies of both sides, Drancejko and the other boys found their way home, and the Russians were gone the next morning.

“At schools we learned that where an artillery shell hits, that’s where we’d go to hide. Bombs couldn’t hit exactly the same place twice, so we’d jump into the hole. We were smart, we figured.”

Of the rest of the year, he remembers that the standing crops in the collective farms were divided, so much for each member of a family. But, by fall he learned that the Germans were no better than were the Russians.

“We had to give, give, give. They needed the food for the soldiers at the front. They took everything: food, cows, even the sheepskins. They needed the sheepskins for their soldiers to wear. The Nazis were cold. They were not prepared for the weather.”

Drancejko stayed in his village, helping with the harvest, finding enough food to keep alive until March 1942 when the Germans wanted able-bodied persons as a free labour force.

“Each village had a quota to meet. Our village’s quota was 116. I was one of 116 people from the village forced to work for the Germans.”

He remembers it was April 28, 1942, a Monday. He had been told to take enough food for two weeks. There was a long walk in the rain (“muddy like hell; up to our knees in mud”) to the train station and overnight. The next day they walked to the Polish border and onto a train.

“It was a cattle car. It was cleaned out. Straw was added. Everyone from a village was kept together in one car. We had 116 from our village in our car.”

The train travelled west from one stop to the other through Ukraine and into Austria. At each stop the people ware disinfected, their hair was cut and then they were re-loaded. The journey ended at Linz, Austria.

After more long walks and many days, Drancejko ended up on a mixed farm where he was to live with two other Ukrainians, a Pole and three Germans, already working for the farmer, his wife and six children.

“We were forced labour.”

On the farm the work began before dawn and lasted until after sunset. Drancejko’s job was to look after 20 to 30 cattle and although it was forced, here at last there was some food.

“We on the farms were the lucky ones. Those who were forced to work in the factories were worse off. They had hard, long hours and poor food. Many died when the factories were bombed.

“Later I learned that at school we had been told lies. They said that other countries had nothing; that the best country was Russia. That was a lie. All the other countries were better.”

By the summer of 1944, he and some of the other older boys on the farm began to talk about escaping the Germans, about running away to join the underground, maybe to fight with General Tito in Yugoslavia.

The farm’s older boys, including Drancejko, agreed to help a soldier who had deserted from the German army. They hid him and carefully reserved a portion of food for him every day for three months, knowing that if found out, death would be the penalty.

They also knew that death awaited them if caught after running away from the farm.

They chose to flee on a Sunday, when the farmer was away. They left, the three of them, on to one farm, and then on to another farm, picking up someone else and on to another farm, for bread, rest and south to Yugoslavia, only about 50 miles away, armed with only “bare hands and sticks.”

Eventually, thanks to a rifle stolen from here, a knife from there, about half the boys in the group ended up with weapons.

He remembers one night en route to Yugoslavia.

“We thought we were safe, that we had picked a good place,” he said of a farm they had come upon. “But it wasn’t like we figured it to have been. We were reported.”

They had just begun to wash up when one of the boys posted outside came running with the bad news: “Army headed this way; maybe 50 of them.”

Into a ravine and hiding in the trees, Drancejko could see the German troops quite well. They ran, but soon came upon a roadblock of four German soldiers.

“We had about 10 Italian rifles. They weren’t very good, but they could shoot.”

They took aim and shot.

Drancejko knows that one German soldier was killed, another, wounded, and the ex-farm labourers escaped.

He was left with the feeling that the Germans could easily have found and killed them, but didn’t bother.

“Why didn’t they make their move? I don’t know. Could it have been that they knew it was the end of the war and they didn’t give a damned anymore?”

The group made it safely to Yugoslavia but it wasn’t long before Drancejko realized that Tito’s underground, striving to establish a communist government, was not to his way of thinking. He said he had already experienced communism, Stalin’s communism, and didn’t want to chance going back to that life.

He went, instead, to Italy where in March he was “handed over” to the Polish Second Army Corps to begin eight weeks of training.

The Second World War, and his training to become a soldier, ended at about the same time.

Coincidentally, while in Italy, Drancejko had been posted at Rimini where Sid Woodward of Kamsack, the oldest brother of the man whose business Drancejko would later purchase, was killed. He was also at Ancona, where Woodward is buried.

When the war ended, he was posted in Bologne, an area fortified by Italian communists, looking after army stores until late 1946 when his detachment was sent to England, his home for the next six years, first in military camps in Norfolk and Suffolk, then working on farms, growing sugar beets and carrots “for a shilling a day.”

When the Polish army was dismantled, he stayed on in England, working, rebuilding a seawall in Essex, rather than emigrate to North or South America like many others in his situation were doing.

“After the war, people like me, the younger people who had survived, were handed over by the English and Americans to the communists for forced repatriation. Few escaped.

“Those people never saw their homes. They were put on trains to Siberia. Premier Nikita Khrushchev gave them amnesty in 1963; amnesty after 18 years, but how many were still alive? I don’t know.

“We didn’t do anything wrong, but they wanted to punish us because we had been outside the Empire. We had seen something other than what we had been told, and because they wanted free labour.”

By 1949, Drancejko had a job in a bakery in Essex. He worked, learned the baking trade, “saved every penny,” and in 1952, making his third attempt to come to Canada, he went to the Canadian embassy in London. In a very short time he was in Canada, finding his way to Winnipeg.

In June 1953, he had read an advertisement for a baker’s helper needed in Swan River. Percy Woodward, the brother of Bob Woodward, a Kamsack baker, had needed a helper in his Swan River bakery. Drancejko applied for the job and was hired.

Admitting his experiences have made him “different” from other people, Drancejko said that looking back he realizes how much he has.

“I keep busy enough so as not to ruin people’s ornaments nor scratch neighbours’ houses,” he said, offering as advice to “cherish what you have.

“There’s no place on earth compared to this country. We don’t know how lucky we are. Many don’t even bother to find out; they take things for granted.

“Canada is a show home among nations.

“Remember, in war, we all lose. When there is war, there is no school, no money, nowhere to go. Millions like us suffered the same fate. We had to do the best we could.

“Some starved, some were killed in the bombing, many suffered from forced repatriation; very few were as lucky as I was.”